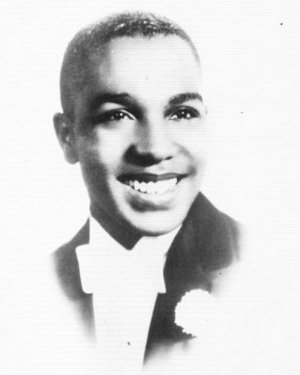

Bon Bon

-

Birth Name

George Nathaniel Tunnell -

Born

June 29, 1912

Reading, Pennsylvania -

Died

May 20, 1975 (age 62)

Lower Merion Township, Pennsylvania -

Orchestras

Sonny James

Jan Savitt

Johnny Warrington

Best remembered for his work with Jan Savitt’s orchestra, Bon Bon was among the first three African-American singers to tour with a white band.[1] After a very successful career as a member of the Three Keys in the early 1930s, Bon Bon joined Savitt’s radio orchestra and proved popular as its featured vocalist when the band went out on its own in early 1938. Discrimination plagued his time with Savitt, however, and he eventually returned to his native Philadelphia. After making one more attempt to sing with a white orchestra in 1944 and facing the same problems, he settled back in Philadelphia permanently, where he worked locally before finally retiring from show business in 1951.

Born George Tunnell, Bon Bon grew up in the Philadelphia area and began singing as a child, making appearances on The Horn and Hardart Children’s Hour program on local station WCAU in the late 1920s.[2] In the early 1930s, he teamed up with pianist Bob Pease and electric guitarist John “Slim” Furnell to form the Three Keys. Using no written arrangements, the trio featured harmony singing and a unique sound described as a “new mode of instrumentation.”

The Three Keys quickly became popular in the Philadelphia area. In 1932, they began appearing on local radio station KYW, an NBC affiliate, where they caught the ear of a network executive who brought them to New York for an audition. They launched their own fifteen-minute nationwide program in August, broadcast from Philadelphia four times a week, and in 1932 they recorded ten sides for Brunswick as well as appeared in the sixth Rambling 'Round Radio Row short. They recorded for Vocalion in 1933. The trio moved to New York in 1934 before heading to Europe, where they played London’s Palladium and gave a command performance for King Edward VIII. They also performed over British and French radio.

Early Band Career

Upon their return to Philadelphia, Bon Bon became a vocalist with the KYW studio orchestra, led by Jan Savitt, which was also broadcast on NBC but later moved to WCAU and CBS. When Savitt decided to take his band, the Top Hatters, on the road in 1938 and seek national recognition, Bon Bon went with him, making him one of the first African-American vocalists to regularly appear with a white orchestra. Able to sing both sweet and swing as well as scat, he proved a sensation during the band’s debut at the Lincoln Hotel in New York’s Times Square and quickly become one of the most well-known and popular vocalists in the nation. He placed fifth in Billboard magazine’s 1940 college poll for most popular male band singers and sixth in 1941. Bon Bon earned third place in Down Beat magazine’s poll for best band vocalist in 1939 and 1940.

As a black performer in an otherwise all-white band, Bon Bon faced much discrimination on the road. He often pretended to be the band manager’s valet in order to stay in the same hotel as the others. He refused to go much further, however, and didn’t tolerate the racism he came up against. During a performance in Kentucky, after he was refused service by the ballroom’s soda stand, he boycotted the show, only appearing on stage to sing during the thirty minutes of the band’s national radio broadcast.

Savitt was disliked by many of his musicians and vocalists, and the Top Hatters had a high turnover. Bon Bon became infamous for quitting and rejoining Savitt’s orchestra numerous times, often returning to Philadelphia to sing with the Three Keys again. In September 1940, he left Savitt, along with African-American arranger Eddie Durham. The two men initially joined Sonny James, an accordion-playing bandleader best known for his Atlantic City orchestras, but by December Durham had organized his own band in order to back Bon Bon. The outfit played the Howard Theater in Washington and then the Royal Theater in Baltimore before folding at the end of the year.

Early 1941 found Bon Bon solo on the same bill as Tony Pastor’s band at the Hotel Lincoln, which came with national airtime.[3] During this period, ASCAP, the songwriter’s performing rights organization, instituted a boycott against radio stations, demanding increased royalties. Vocalists and musicians faced restrictions on performing ASCAP-controlled songs during broadcasts. A well-known scat singer, Bon Bon suddenly found himself unable to scat, improvise, or ad lib on any song he sang on the radio. He had to perform every number straight. “I don’t feel it,” he told Down Beat magazine, “but I’ll do the best I can until I can use my own style again.”

In July 1941, Bon Bon recorded for Decca with a studio band under the name Bon Bon and His Buddies.[4] Both Bon Bon and Durham rejoined James again at some point in 1941, but by October Bon Bon had returned to Savitt, staying only a few months, however, before quitting for good in February 1942. He told Down Beat that he was taking the civil service exam in hopes of working at the post office. “I’m sick and tired of banging around the country, and I want to be near that youngster of mine all the time,” he said, referring to his new son, born that past November.

Post-Savitt Years

After returning home, Bon Bon began a solo act at the popular Philadelphia nightclub Lou’s Moravian Inn, which would become his home away from home for many years to come. Slated for an NBC Blue Network program, he returned to KYW, singing with their then current studio orchestra, led by Clarence Fuhrman. In January, he had cut more recordings on Decca under the band name Bon Bon and His Buddies, still using a studio crew. A four-piece band bearing that name made its live debut in April 1942 at Lou’s and later expanded to a six-piece combo. They appeared on local television station WPTZ as well.

In May 1942, Bon Bon moved to radio station WCAU, where that summer he hosted Dixiana, the first all-African-American variety program ever produced in the city. The show ran off and on over the next year. He also continued working with his band around the Philadelphia area, performing mostly at Lou’s. He remained popular in his home city but struggled to gain the same national following that he had earned with Savitt. His band signed with the Fredericks Bros. agency in March 1943 and made a New York appearance, but he was soon back in Philadelphia again.

In late 1943, Bon Bon began singing for WCAU’s studio orchestra, led by Johnny Warrington, a former Savitt musician. An exciting band, Warrington began to tour regionally, taking Bon Bon with him. In summer 1944, Bon Bon once again faced racism when he was denied the chance to sing at Atlantic City’s famous Steel Pier due to its policy of allowing only white performers on its stage. He quit Warrington soon after and returned to Philadelphia.

Post-Band Career

After leaving Warrington, Bon Bon began to work on and off with the Four Keys again, the current expanded version of his old group, also performing solo and with other area bands. In September 1944, he signed to a multi-year contract with Beacon Records, one of the small labels run by music publisher Joe Davis with the express purpose of plugging his songs. Bon Bon became one of Davis’ most used pluggers, making multiple recordings over the next four years on both Beacon and the Joe Davis label as well as Celebrity, another Davis imprint. His records were popular in Philadelphia but made no impact nationally. He also recorded on the local Melody and 20th Century label with the Four Keys. In 1947, he signed a solo contract to record on the local Savoy label.

Bon Bon made another attempt to front his own orchestra in mid-1945, partnering with Durham again, who had just scrapped his all-girl outfit. The sixteen-piece band played several one-nighters in Florida during October but failed to catch on. In mid-1949, Bon Bon and the Keys, as they were called by this time, worked a month in Las Vegas.

In August 1948, Bon Bon signed with Philadelphia radio station WDAS to star in his own program. The Bon Bon Show both featured musical performances and served as a community service show for the city’s African-American community. Bon Bon would often take a tape recorder out onto the street and ask passers-by their opinions. The show was popular enough that WDAS gave it a second weekly edition in April 1950. By the end of the year though, Bon Bon had moved to WPEN to work as a DJ before unsuccessfully attempting to launch a solo music career again. He finally retired from show business in April 1951, taking a job as assistant district manager for the Eastern Division of Schlitz breweries.

Bon Bon passed away in May 1975 at the age of 62.[5]

Notes

Bon Bon was the first male African-American vocalist with a white band. June Richmond became the first African-American to sing with a white orchestra in 1937. Both Bon Bon and Billie Holiday, who was with Artie Shaw, began to tour with white bands at approximately the same time in early 1938, though Bon Bon had been with Savitt since at least 1937 and had performed locally with the band. ↩︎

The name Bon Bon is a reference to the chocolate covered candy. Bon Bon told that he once sang for a candy sponsor in Philadelphia who gave him the name. African-American performers during this time period often used references to chocolate in names and titles. The late 1920s all-black revue Hot Chocolates at one time featured a singing group called the Bon Bon Buddies, a moniker tracing back to a popular song written in 1907. Some historians have confused the singer Bon Bon with this group due to his forming a combo known as Bon Bon and His Buddies in the early 1940s. He had no connection to the New York group however. The name Bon Bon itself was used by several performers over the years, including a popular white stripper in the 1950s. ↩︎

Backing Bon Bon at the Hotel Lincoln were the Lincolnaires, a five-piece combo, all of whom, except for guitarist Dave Barbour, were former, disgruntled Savitt musicians. ↩︎

Included in those recordings was the song “I Don’t Want to Set the World on Fire.” Bandleader Tommy Tucker and singer Amy Arnell had heard Bon Bon perform the song live in 1940 and had recorded it on Okeh in early 1941, selling over 500,000 copies. ↩︎

Some sources give Bon Bon’s birthdate as June 30. Philadelphia city birth records give it as June 29. ↩︎

Sources

- Simon, George T. The Big Bands. 4th ed. New York: Schirmer, 1981.

- “Bon Bon.” IMDb. Accessed 29 Jul. 2016.

- “The Three Keys, Radio's Latest Sensation.” The Afro-American [Baltimore, Maryland] 20 Aug. 1932: 7.

- “Notes for Coming Week.” The Montreal Gazette 20 May 1938: 10.

- “On the Stage.” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette 11 Aug. 1938: 9. Print

- McClarrin, Otto. “Otto McClarrin's Seaboard Merry-Go-Round.” The Washington Afro-American 18 Feb. 1939: 6.

- Egan, Jack. “Here's Lowdown Stuff on Nation's Radio Eds.” Down Beat 15 May 1940: 6.

- Davis, Dotty. “Bon Bon May Leave Savitt Soon.” Down Beat 15 Aug. 1940: 13.

- “Bon Bon with Sonny James So is Durham.” Down Beat 1 Oct. 1940: 8.

- “Bon Bon-Jan Are Parted.” Down Beat 1 Nov. 1940: 1.

- “Bon Bon Leaves Savitt.” The Afro-American [Baltimore, Maryland] 2 Nov. 1940: 14.

- “Bon Bon, Eddie Durham in Debut.” Down Beat 15 Dec. 1940: 9.

- “Durham-Savitt Settle Cash Fight.” Down Beat 1 Jan. 1941: 1.

- “They Are Fugitives From Jan Savitt.” Down Beat 15 Jan. 1941: 2.

- “No Scats for Bon Bon on Broadcasts.” Down Beat 1 Feb. 1941: 2.

- “Bon Bon Back With Savitt.” Down Beat 1 Nov. 1941: 1.

- “It's a Boy For Bon Bon.” Down Beat 1 Dec. 1941: 4.

- “Night Club Reviews: Sherman Hotel, Panther Room, Chicago.” Billboard 7 Feb. 1942: 13.

- “On the Records.” Billboard 21 Feb. 1942: 66.

- Jovien, Harold. “Bon Bon Reveals Desire For Postman's Berth As He Leaves Jan Savitt.” Down Beat 1 Mar. 1942: 2.

- “On the Records.” Billboard 14 Mar. 1942: 25.

- “Record Reviews: Bon Bon and His Buddies.” Down Beat 15 Mar. 1942: 14.

- “Bon Bon, Hot Singer, Back in Pa.” The Afro-American [Baltimore, Maryland] 21 Mar. 1942: 15.

- “Advertisers, Agencies, Stations.” Billboard 21 Mar. 1942: 6.

- “On the Stand: Bon Bon and His Buddies.” Billboard 11 Apr. 1942: 22.

- “Orchestra Notes.” Billboard 25 Apr. 1942: 23.

- “Campus Picks Top Chirps.” Billboard 2 May 1942: 19.

- “Advertisers, Agencies, Stations.” Billboard 23 May 1942: 8.

- “Advertisers, Agencies, Stations.” Billboard 4 Jul. 1942: 6.

- “Orchestra Notes.” Billboard 1 Aug. 1942: 23.

- “Bon Bon Heads Philly Air Show.” Down Beat 1 Aug. 1942: 12.

- “Program Reviews: Dixiana.” Billboard 15 Aug. 1942: 8.

- “Orchestra Notes.” Billboard 12 Sep. 1942: 21.

- “Four Keys Originated in Philly.” The Afro-American [Baltimore, Maryland] 19 Sep. 1942: 12.

- “Big Tea Packs Shangri-La in Philadelphia.” Down Beat 1 Dec. 1942: 23.

- “Off the Cuff.” Billboard 26 Dec. 1942: 18.

- “Off the Cuff.” Billboard 20 Feb. 1943: 19.

- “Program Reviews: Open House.” Billboard 27 Feb. 1943: 9.

- “Nucleus of Savitt Crew Sparks Warrington Ork In Philly Radio Station.” Down Beat 15 Mar. 1943: 13.

- “Bon Bon Leads Combo Again.” Billboard 27 Mar. 1943: 18.

- “No Time to Fill, But Lee Broza Buys New Talent.” Billboard 16 Oct. 1943: 7.

- “On the Stand: Johnny Warrington.” Billboard 16 Oct. 1943: 16.

- “Talent-Hungry Radio Lanes Turn To Rich Unit Pasture.” Billboard 23 Oct. 1943: 22.

- “Program Reviews: Dixiana.” Billboard 6 Nov. 1943: 11.

- “Philly Earle Light $17,800, Fay's 96C.” Billboard 27 Nov. 1943: 17.

- “List of Winners: Collegiate Choice of Vocalists.” The Billboard 1943 Music Yearbook, 1943: 139.

- “Sepia Singer Banned From Pier Ballroom.” Down Beat 1 Aug. 1944: 1.

- “Hate Policy Bans Bon Bon.” The Afro-American [Baltimore, Maryland] 12 Aug. 1944: 8.

- “Philly Cocktaileries Bring Back Talent.” Billboard 12 Aug. 1944: 29.

- “Bon-Bon Contracted to Cut 16 Disks Yearly for Beacon.” Billboard 23 Sep. 1944: 36.

- “Off the Cuff.” Billboard 23 Sep. 1944: 37.

- “Off the Cuff.” Billboard 21 Apr. 1945: 28.

- “Bon Bon Fronts New Ork.” Billboard 14 Jul. 1945: 66.

- “Bon Bon and His 16.” Billboard 29 Sep. 1945: 32.

- “Music as Written.” Billboard 20 Oct. 1945: 24.

- “Analyzing Band Poll.” Down Beat 15 Jan. 1947: 17.

- “Magee Toots Again in Philly.” Down Beat 12 Mar. 1947: 18.

- “Adanced Record Releases.” Billboard 3 Apr. 1948: 126.

- “Back Stage Whispers Got Peggy a 'Break.'” The Baltimore Afro-American 8 Jun. 1948: 6.

- “1-Hour Daily Negro Service Program Skedded by WDAS.” Billboard 13 Aug. 1948: 6.

- “No New Quintet for Public.” Billboard 4 Dec. 1948: 20.

- “One More Philly Station Junks Studio Orchestra.” Down Beat 1 Jul. 1949: 19.

- “Only A Change in Owners Halts Hugo's 12-Year Job.” Down Beat 12 Aug. 1949: 11.

- “Deejay Bon Bon Spots Savitt Wax.” Down Beat 23 Sep. 1949: 18.

- “Vox Jox.” Billboard 29 Oct. 1949: 26.

- “Music as Written.” Billboard 12 Nov. 1949: 42.

- “Vox Jox.” Billboard 1 Apr. 1950: 24.

- “Music as Written.” Billboard 9 Dec. 1950: 17.

- “Music as Written.” Billboard 5 May 1951: 18.

- “No Title.” Down Beat 1 Jun. 1951: 12.

- “Pennsylvania, Philadelphia City Births, 1860-1906,” FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:QP7T-RP3N : Fri May 17 18:48:15 UTC 2024), Entry for Tunnel and Warren Tunnel, 29 Jun 1912.

- “United States Census, 1920,” FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:MFTH-6Z3 : Sun Mar 10 17:27:06 UTC 2024), Entry for Warren Tunnell and George Tunnell, 1920.

- “United States Census, 1930,” FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:XH4F-SFP : Thu Mar 07 20:56:59 UTC 2024), Entry for Warren Tannell and Catherine Tannell, 1930.

- “United States Social Security Death Index,” database, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:JRCZ-3JD : 8 January 2021), George Tunnell, May 1975; citing U.S. Social Security Administration, Death Master File, database (Alexandria, Virginia: National Technical Information Service, ongoing).