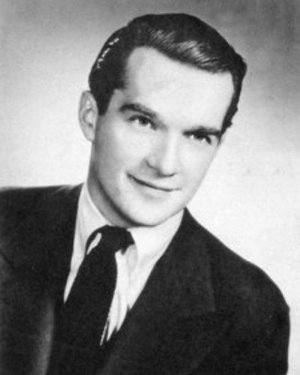

Jack Leonard

-

Birth Name

John Joseph Leonard -

Born

February 10, 1913

Brooklyn, New York -

Died

June 17, 1988 (age 75)

Woodland Hills, California -

Orchestras

Bert Block

Tommy Dorsey

Vocalist Jack Leonard is best remembered for his time with Tommy Dorsey’s orchestra in the late 1930s, during which he rivaled Bing Crosby as the country’s top male singer. After Dorsey fired him in late 1939, he began a successful solo career cut short by the draft in 1941. Leonard spent the entire war in the service. Discharged at the end of 1946, he tried to resurrect his career, but both the public’s taste and the music industry had changed too much. Leonard kept trying into the early 1950s before finally giving up.

Leonard got his start singing at a roadside stand on Long Island and worked on the government relief team that built New York’s Jones Beach in the early 1930s. He was singing in Bert Block’s orchestra when Dorsey hired him away in early 1936. Dorsey also took trumpeter Joe Bauer and arranger Axel Stordahl, then known as Odd Stordahl. Together the men formed a vocal group call the Three Esquires.

It was as a soloist, though, that Leonard would achieve stardom, singing on such classics as “Marie,” “All the Things You Are,” “Our Love,” and “Indian Summer.” He quickly became popular with audiences and critics alike and placed at or near the top in various polls conducted during the late 1930s. He was rivaled only by Bing Crosby in popularity.

Leonard was a shy, handsome man who was liked by all. He was very near-sighted but refused to wear glasses in public so as not to spoil his romantic image. His departure from Dorsey’s orchestra in November 1939 was a surprise to his bandmates. The rumor was that Dorsey had grown suspicious of Leonard’s intentions, fearing that he was going to leave soon for a solo career, and had forced him out. Leonard himself tried to dispel that rumor at the time, saying he just needed a break and would return soon, and indeed an announcement was made a week later that Leonard and Dorsey had patched up their differences and that Leonard would return to the band permanently. He never did.

Dorsey had just lost his other long-time vocalist, Edythe Wright, the previous month and used the opportunity of shedding Leonard to revamp his entire orchestra, which may have also played a part in the singer’s departure. An unusual quirk in the matter was that Dorsey held Leonard’s personal management contract, meaning that he would get a cut of anything Leonard made as a solo artist. Leonard was replaced in Dorsey’s band by Allan DeWitt, who failed to work out and was replaced after less than two months by Frank Sinatra.[1]

Early Solo Career and War Years

Leonard’s popularity kept him busy after leaving Dorsey. He worked steadily on radio, appearing three times a week on CBS. When Leonard wasn’t on the radio he was either in theaters or in the recording studio for Okeh Records. He also reportedly began dating singer Amy Arnell. His career and personal life were going strong until early March 1941, when, on the same day that he screen-tested for 20th Century Fox and signed on for appearances at New York’s Paramount Theater for $350 a night, Leonard received his draft notice. He managed a deferment until May to complete his Paramount obligations and then reported for duty. His draft board proposed putting him in an Army entertainment unit, though Leonard refused. He ended up singing anyway, at Fort Dix, New Jersey, for the Herbie Fields band.

Leonard’s initial period in the Army had little effect on his popularity. Soon after he entered the service, Okeh gained permission to bring him into the studio while he was in uniform, which helped keep his name in circulation. The Army then released him in November, before his year was up, because he was over 28 years old, and he quickly returned to civilian life and resumed his career, beginning a series of theater dates and cutting several more sides for Okeh. He was also in the running for his own NBC radio program. In the wake of Pearl Harbor, though, the Army recalled him to active duty in January 1942, and back to Fort Dix he went, this time for the duration of the war.

Popular with other soldiers, Leonard rose to the rank of staff sergeant. He soon found himself fronting his own band, which kept him busy hosting a nightly variety show and doing four radio broadcasts a week, including one for the Mutual network. The band traveled to Europe in early 1945, returning in August for reassignment. Discharged soon after, Leonard attempted to restart his career after five years of inactivity.

Post-War Years

Before Leonard had even received his discharge papers, networks had begun feeling him out for a radio program. In December, he signed a two-year deal with Majestic Records, and his first live booking happened on January 3 at the Copacabana in New York, where he took second billing after Jerry Lester when Phil Regan refused to accept the spot. There was great expectations for Leonard among audiences and critics, but he would soon disappoint. His 1946 recordings sounded similar to the romantic ballads of his pre-war material but lacked warmth, and when they failed to capture any attention 1947 saw a complete shift in style to light-hearted material backed by a jazzy vocal quartet, which equally failed to impress.

Leonard made three minor silver screen appearances starting in 1947, his first as a singing cowboy in a film titled Swing the Western Way. All were B movies. Majestic dropped him after his contract ended, and he signed with Hi-Tone in 1949 and also recorded with Signature later that year. The records received little notice. He had his own television program in 1949 and appeared as one of the hosts for Broadway Open House in 1951, but despite his best efforts he was never able to regain the traction he had prior to the war.

Leonard made a return to the recording studio with Dorsey in 1951. The bandleader arranged the sessions as a way to help boost Leonard, but the records, old-fashioned in their attempt to mimic the 1937 hit “Marie,” went nowhere. When Dorsey offered Leonard the job of advance radio promotion man for the band in 1952, Leonard accepted, retiring from the stage. Leonard’s duties were to precede the band into town at their next scheduled performance and hit the airwaves to promote the show, a job that he loved. He only occasionally sang thereafter, most notably in 1956 when he performed at the memorial concert after Dorsey’s death.

Leonard later served as Nat King Cole’s business manager and worked in music publishing before retiring in the 1970s. He married Edna Ryan in July 1948. Jack Leonard died from cancer in 1988, age 75.[2]

Notes

It’s an oft-repeated falsehood that Sinatra replaced Leonard in Dorsey’s band. The story is also sometimes told that Leonard left Dorsey because he was drafted, which is even less true. The events that surrounded Leonard’s departure from the orchestra were major news events and clearly reported at the time but became distorted by the late 1940s, with even trade magazines and jazz “historians” misremembering the correct story. Leonard himself tied into this narrative, and these falsehoods have been perpetuated over the years by newspaper articles, obituaries, and sloppy historical work. ↩︎

Many sources give the year of Leonard’s birth as 1915, and obituaries say he was 73 when he died in 1988. Public records, however, show that he was born in 1913, which his grandson has also stated. Leonard most likely, when attempting to resurrect his career post-war, misrepresented his age to appear younger, a not uncommon practice for celebrities at that time. ↩︎

Sources

- Simon, George T. The Big Bands. 4th ed. New York: Schirmer, 1981.

- Walker, Leo. The Wonderful Era of the Great Dance Bands. Garden City, New York: Doubleday, 1972.

- McCarthy, Albert. The Dance Band Era. Radnor, Pennsylvania: Chilton, 1971.

- “Jack Leonard.” IMDb. Accessed 9 Nov. 2015.

- The Online Discographical Project. Accessed 9 Nov. 2015.

- “Orchestra Notes.” Billboard 18 Nov. 1939: 10.

- “Orchestra Notes.” Billboard 25 Nov. 1939: 12.

- “Jack Leonard Back With T. Dorsey.” Down Beat 1 Dec. 1939: 2.

- Thompson, Edgar A. “Riding the Airwaves.” The Milwaukee Journal 8 Dec. 1939: 2.

- “Tom Dorsey Gets Frank Sinatra.” Down Beat 1 Feb. 1940: 5.

- “Comment.” Billboard 10 Feb. 1940: 8.

- “Jack Leonard Drafted; Movies Want Him, Too.” Down Beat 15 Mar. 1940: 2.

- “Orchestra Notes.” Billboard 14 Sep. 1940: 11.

- Steinhauser, Si. “Star Gets Ready for Army Pay.” The Pittsburgh Press: 12 May 1941: 16.

- Advertisement. Billboard 25 May 1940: 13.

- “Vaude Names' Prices Soar.” Billboard 1 Mar. 1941: 17.

- “Ravings at Reveille.” Down Beat 1 Jun. 1941: 11.

- Egan, Jack. “Egan Excreta.” Down Beat 15 Jun. 1941: 4.

- “Jack Leonard.” Down Beat 15 Jul. 1941: 12.

- “Talent and Tunes On Music Machines.” Billboard 2 Aug. 1941: 71.

- “On the Records.” Billboard 16 Aug. 1941: 71.

- “Leonard Booked for Strand.” Billboard 15 Nov. 1941: 13.

- “Jack Leonard and Don Matteson Shed Khaki, Leave Dix.” Down Beat 15 Nov. 1941: 5.

- “Jack Leonard Back in Action.” Down Beat 1 Dec. 1941: 1.

- “Ex-Draftees Await Recall To Fight War, Unk.” Down Beat 1 Jan. 1942: 3.

- “Talent and Tunes On Music Machines.” Billboard 10 Jan. 1942: 65.

- “Jack Leonard Is Ready, Unk.” Down Beat 15 Jan. 1942: 23.

- “Sergeant Leonard Reports for Duty.” Down Beat 1 Feb. 1942: 21.

- “Ravings at Reveille.” Down Beat 1 Mar. 1942: 21.

- “Ace Musicians and Star Performers Give Fort Dix Plenty of Entertainment.” Down Beat 1 Nov. 1942: 19.

- “Ravings at Reveille.” Down Beat 15 Feb. 1943: 16.

- “Ravings at Reveille.” Down Beat 1 Aug. 1943: 20.

- Lino, Al. “Dorsey Worried Because Vocalists Are Too Good.” St. Petersburg Times [St. Petersburg, Florida] 26 Mar. 1944: 43.

- “Ravings at Reveille.” Down Beat 15 Mar. 1945: 13.

- “Singer Jack Leonard Back From The Wars.” Down Beat 15 Aug. 1945: 3.

- “Strictly Ad Lib.” Down Beat 1 Oct. 1945: 1.

- “Jack Leonard Inks Majestic Disk Pact.” Billboard 1 Dec. 1945: 18.

- “Jack Leonard Bows At Copa.” Down Beat 14 Jan. 1946: 3.

- “Diggin' the Discs.” Down Beat 11 Feb. 1946: 8, 19.

- “Percy Faith Carries On Tradition of 'Big 4'.” Down Beat 29 Jan. 1947: 19.

- Emge, Charles. “On the Beat in Hollywood.” Down Beat 12 Mar. 1947: 9.

- “Tied Notes.” Down Beat 22 Sep. 1948: 10.

- “Leonard Recalled To Nitery In Pittsburgh.” Down Beat 22 Sep. 1948: 8.

- “Strictly Ad Lib.” Down Beat 15 Jul. 1949: 12.

- “Strictly Ad Lib.” Down Beat 4 Nov. 1949: 5.

- “Record Reviews.” Billboard 22 Dec. 1951: 32,33.

- Holly, Hal. “Jack Leonard, TD Road Mgr., Happy To Be An Ex-Singer.” Down Beat 2 Jul. 1952: 5.

- “Strictly Ad Lib.” Down Beat 19 Sep. 1956: 8.

- “Nat May Bite.” Down Beat 21 Aug. 1958: 10.

- “Obituaries : Jack Leonard, 73, Big Band Singer.” Los Angeles Times 19 Jun. 1988. Web.

- “Jack Leonard, Singer, 73.” The New York Times 22 Jun. 1988. Web.

- “New York State Census, 1915,“ database, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:K9R9-PX4 : 3 June 2022), John Leonard in entry for John J Leonard, 1915.

- “United States Census, 1920,” FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:MJRY-18Q : Sun Mar 10 12:18:42 UTC 2024), Entry for Jersham Leonard and Mabel Leonard, 1920.

- “United States Census, 1930,” FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:X78L-SXN : Fri Mar 08 07:56:53 UTC 2024), Entry for John Leonard and Mabel Leonard, 1930.

- “United States Census, 1940,” FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:K3Y1-R5Z : Sun Mar 10 10:13:04 UTC 2024), Entry for John J Leonard and Mabel Leonard, 1940.

- “United States, Social Security Numerical Identification Files (NUMIDENT), 1936-2007,” database, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:6K9S-GWFK : 10 February 2023), John Joseph Leonard.

- “California Death Index, 1940-1997,” database, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:VPJM-7LD : 26 November 2014), John Joseph Leonard, 17 Jun 1988; Department of Public Health Services, Sacramento.