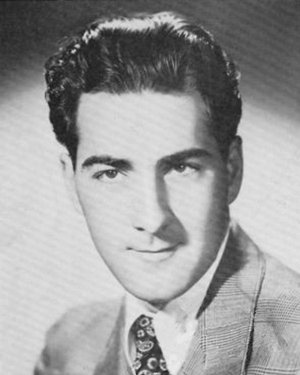

Teddy Walters

-

Birth Name

Walter Alvin -

Born

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania -

Orchestras

Jimmy Dorsey

Tommy Dorsey

Gene Krupa

Guitarist Teddy Walters created a major sensation in November 1943 when he got up for the first time to sing with Tommy Dorsey’s band. Critics and music fans alike proclaimed him the greatest find in recent years, and for a brief period Frank Sinatra had to keep looking over his shoulder as the younger Walters threatened to end his reign as the king of swoon. Unfortunately, it wasn’t to be. Walters lacked the professional training of a vocalist and was never able to translate his initial momentum into a long-term career as a singer. After moving on to Jimmy Dorsey’s band, where he spent more than a year, Walters’ solo career quickly fizzled.

A Philadelphia native and the son of famous Dixieland drummer Danny Alvin, Teddy Walters worked with several bands, including those of Ray Noble and Raymond Scott, before joining fellow Philadelphian Charlie Ventura’s first orchestra in May 1942, where he received feature billing.[1] Walters was chiefly a guitarist, though he had on occasion sang with Noble’s band. Walters’ guitar skills were what attracted the attention of Gene Krupa, who quickly signed him away from Ventura. When Krupa singer Johnny Desmond received his draft notice, Walters filled in at the mike. The band’s vocal arrangements were in Desmond’s key, however, and Walters didn’t fare well with the material. After Krupa brought in Ray Eberle as a permanent replacement, Walters decided to give up on singing. He left Krupa soon after.

Walters joined Les Brown in April 1943, staying through at least June. He then took time out from working with bands to trade his Philadelphia union card for a local New York version. During the waiting period to received his new card, Walters played guitar for small combos to keep in practice. He quickly gained a reputation for his skills and finally found himself working with Ben Webster’s five-piece outfit at the Three Deuces night club on 52nd Street, where he rubbed elbows with such jazz greats as Billie Holiday and Coleman Hawkins.

Walters attracted the attention of Jack Gale, who became his manager. Gale found Walters extra work writing guitar technique books for music publisher Jack Robbins. One day in late 1943, Gale heard Walters sing while at the Robbins music office and brought it to the attention of Robbins himself. The two men encouraged him to sing more often, and he began to do a few numbers at the Three Deuces. Robbins and Gale invited Tommy Dorsey to the club to take a listen, and after hearing only one number the bandleader asked Walters “When do you want to begin?”

Overnight Fame

Walters joined Dorsey in November 1943 at a time when the bandleader was having trouble finding suitable male vocalists. When he put Walters in front of the mike, the audience went wild. With a voice similar to that of Sinatra, so much so that even critics had a hard time telling them apart, Walters became an overnight sensation. Dorsey knew a good thing when he saw one and offered Walters a long-term contract of either five or seven years, depending on the source, with the bandleader taking a percentage of Walters’ future earnings should he go solo. Gale refused anything less then three years. Walters left the band over the dispute but then returned before leaving again at the first of the year rather than sign.[2]

Dorsey tried several times over the next few months to get Walters back but to no avail. Walter certainly didn’t lack for work. American Tobacco, the sponsor of Your Hit Parade, signed him as Sinatra’s stand-in should something happen to the more famous singer, who was then the current host of the show.[3] By March, he was singing at the La Conga club in New York and had switched managers from Gale to Robbins. Walters also kept busy as a musician on recordings with Cozy Cole and as part of Keynote’s jazz sessions disks. He also co-wrote, with Sid Robin, the song “(Yip Yip De Hootie) My Baby Said Yes,” made popular by Bing Crosby and Louis Jordan that year.

Walters eventually ended up in the Dorsey fold once again, though this time with Jimmy. He signed with the elder Dorsey’s band in June 1944 as a singer, sometimes accompanying himself on the guitar. Again he caused a sensation. Audiences couldn’t get enough of his voice, demanding encore after encore. Critics also loved him. One heralded him as the most important male band vocalist of the last three years, though many noted his stiffness at the mike. Not trained as a professional singer, Walters’ delivery and general appearance were often rough.

Walters remained with Jimmy Dorsey until August 1945 when he left to go solo.[4] He recorded with Tommy Todd in December 1945 and under his own name for the ARA label in early 1946. He also played guitar for a Billie Holiday recording and had his own ABC radio program Teddy Walters Presents. Walters both sang and played on his solo recordings, where he was billed as “Teddy Walters, His Voice and Guitar.”

At the start, Walters’ career looked promising. He cracked the Top Ten during the week of April 13, 1946, with his recording of “Laughing on the Outside (Crying on the Inside),” which debuted at number nine on the charts. He signed with Musicraft soon after, where he recorded both solo and with Artie Shaw. None of Walters’ subsequent work, though, caught the public’s interest. He continued with Musicraft into early 1947 and appeared with Boyd Raeburn’s band in a Columbia musical short that same year. In early 1947, he began working with his own small jazz combos, focusing on night clubs. By 1948, his spotlight had faded, and he eventually returned to Philadelphia, where he made a failed comeback attempt in December 1950. In 1954, Walters was working “steadily” as a singer and guitarist at Riff’s, a “sailors’ rendezvous.” He then disappears into the mists of history.

Notes

The 1930 Census, taken on April 3 of that year, lists Walters as ten years old, giving him an approximate birth date range of April 1919 to March 1920. ↩︎

Dorsey had a similar arrangement with Frank Sinatra. Sinatra eventually ended up buying Dorsey out of the contract. Bandleaders often hesitated to invest in building up a singer if they felt that the singer might leave quickly. ↩︎

By July, Walters had terminated his contract with Your Hit Parade due to weeks of “nothing happening.” ↩︎

Down Beat magazine reported that Walters left Dorsey to pursue a “screen career.” If so, nothing ever came of it. ↩︎

Sources

- The Online Discographical Project. Accessed 27 Jan. 2018.

- “Teddy Walters.” IMDb. Accessed 27 Jan. 2018.

- “Philly Jazz Combo Set For Debut?” Down Beat 15 Apr. 1942: 19.

- “Preems Ork in Music Shop!” Billboard 30 May 1942: 21.

- “Orchestra Notes.” Billboard 25 Jul. 1942: 25.

- “Where Is?” Down Beat 15 Aug. 1942: 9.

- “Les Brown Gets Teddy Walters.” Down Beat 1 May 1943: 1.

- “Les Brown Band Splits BallGames.” Down Beat 1 Jul. 1943: 4.

- “Holiday, Hawkins, Webster, Tatum, Pulling 'Em in and Knocking 'Em Out on 52nd St.” Billboard 16 Oct. 1943: 4.

- Stacy, Frank. “Teddy Walters Shakes Himself and Discovers Fame Staring at Him.” Down Beat 15 Nov. 1943: 3.

- “Cat's Corner.” The SaMoJaC [Santa Monica, California] 24 Nov. 1943: 2.

- “Vocalists Balk At Long Pacts.” Down Beat 15 Jan. 1944: 1.

- “T. Dorsey Wants Vocalist Walters.” Billboard 19 Feb. 1944: 13.

- “Keynote Set to Invade Longhair Jive Disk Field.” Billboard 4 Mar. 1944: 15.

- “Walters Warbling At NYC's La Conga.” Down Beat 1 Apr. 1944: 2.

- “Popular Record Reviews.” Billboard 6 May 1944: 19.

- “Sinatra's Stand In.” Billboard 10 Jun. 1944: 11.

- “Walters to Warble for JD.” Billboard 1 Jul. 1944: 15.

- “Teddy Walters Joins Jimmy Dorsey's Ork.” Down Beat 15 Jul. 1944: 1.

- “Teddy Walters To Do Vocals With JD.” Down Beat 1 Aug. 1944: 2.

- “On the Stand: Jimmy Dorsey.” Billboard 12 Aug. 1944: 20.

- “Vaudeville Reviews: Capitol, New York.” Billboard 25 Nov. 1944: 29.

- “Morrow Gets His Break.” Billboard 2 Jun. 1945: 16.

- “Strictly Ad Lib.” Down Beat 1 Sep. 1945: 1.

- “Music as Written.” Billboard 13 Oct. 1945: 21.

- Advertisement. Billboard 15 Dec. 1945: 17.

- “Diggin' the Discs.” Down Beat 22 Jan. 1946: 8.

- “Record Reviews.” Billboard 23 Mar. 1946: 130.

- “Records Most-Played on the Air.” Billboard 20 Apr. 1946: 29.

- “Most-Played Juke Box Records.” Billboard 18 May 1946: 117.

- “Music as Written.” Billboard 8 Jun. 1946: 24.

- “Records Most-Played on the Air.” Billboard 22 Jun. 1946: 28.

- “Advanced Record Releases.” Billboard 13 Jul. 1946: 33.

- “Reviews of New Records.” Billboard 13 Jul. 1946: 34.

- “The Billboard First Annual Music-Record Poll.” Billboard 4 Jan. 1947: 10.

- “Auld, Chaloff, Rodney Sextet Into 3 Deuces.” Down Beat 12 Mar. 1947: 3.

- “Music as Written.” Billboard 22 Mar. 1947: 19.

- “Record Reviews.” Billboard 19 Apr. 1947: 118.

- Haynes, Don C. “Chicago Band Briefs.” Down Beat 18 Jun. 1947: 12.

- “Chi Midnight Concerts Start.” Billboard 8 Jan. 1948: 17.

- Hallock, Ted. “Chicago Band Briefs.” Down Beat 11 Feb. 1948: 4.

- “Strictly Ad Lib.” Down Beat 19 May 1948: 5.

- “Music as Written.” Billboard 16 Dec. 1950: 16.

- “Teddy Walter Working Again.” Down Beat 12 Jan. 1951: 1.

- “Teddy Walter In Comeback.” Down Beat 10 Mar. 1954: 1.

- “United States Census, 1930,” FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:XS5F-N8Z : Sun Mar 10 20:42:37 UTC 2024), Entry for Dan Alvin and Mary Alvin, 1930.