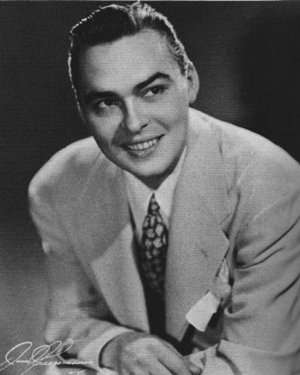

Ray Eberle

-

Birth Name

Raymond Richard Eberle -

Born

January 19, 1919

Mechanicville, New York -

Died

August 25, 1979 (age 60)

Douglasville, Georgia -

Orchestras

Gene Krupa

Jan Garber

Glenn Miller

-

Featured Vocalists

Johnny Bond

Rosemary Calvin

Vocalist and bandleader Ray Eberle is best remembered for his work with Glenn Miller in the late 1930s and early 1940s. In popularity polls, Eberle consistently placed among the top male band vocalists of his era, often sharing honors with his older brother, Bob Eberly, who sang with Jimmy Dorsey’s orchestra.[1] After Eberle and Miller parted ways in mid-1942, Eberle spent time with Gene Krupa before launching a solo career the following year. In 1946, he formed his own orchestra, which struggled before disbanding in 1949. He continued singing and leading bands into the 1970s.

Born in Mechanicville, New York, the Eberle brothers grew up in Hoosick Falls, where the family had moved by 1925 and their father operated a hotel.[2] Ray had no professional experience when he joined Miller in 1937. Miller, looking for a male vocalist for his new orchestra, asked Bob if he had any brothers at home who could sing. Bob said “yes,” and Miller hired Ray based on this recommendation. Miller’s 1937 band failed, but when he formed a new group in 1938 Eberle once again became its vocalist.

Though music critics were often unimpressed with Eberle’s voice, he became an integral part of the Miller line-up, singing on many of the group’s biggest hits. Even Miller’s own musicians weren’t happy with Eberle’s style and often voiced their complaints, but Miller stuck with him. Audiences loved him. He placed second in Billboard magazine’s 1941 college poll for best male band vocalist and won first place in 1942. He placed third in the 1943 poll.

Eberle secretly married Janet Young in January 1940, telling only Miller. The rest of the band didn’t learn about the marriage until summer. The couple actually married twice—the second time just to “be sure.” The couple had a daughter, Raye, in early 1941.

A lack of professional discipline led to Eberle’s departure from Miller’s orchestra in June 1942, though the actual event that caused his dismissal was beyond his control. Stuck in traffic during a Chicago engagement, he was late for rehearsal. Miller fired him on the spot, no questions asked. Eberle responded by blasting Miller in a trade paper. An angry Miller retorted with his own version of Eberle’s firing.

Despite the public rift with his former boss, Eberle soon landed a job with Gene Krupa, where he replaced Johnny Desmond, who had just received his draft notice. In January 1943, Jan Garber attempted to lure Eberle away from Krupa, but the singer and the bandleader had a fight during their first rehearsal, and the deal fell through. Neither would talk about the details. When asked by Down Beat magazine, Garber simply went “into a pantomime act of a guy slightly the worse for wear for one or two too many.” Eberle returned to Krupa, whom he left the next month to go solo when he landed a seven-year contract with Universal Studios. He made five films over the next two years, playing a band vocalist or bandleader in all of them.

Solo Career

On his own as a singer, Eberle continued to perform and tour the country. In April 1943, he worked with the orchestra of Glenn Miller’s brother, Herb. In late 1944 or early 1945, he recorded with the Skylarks and the Buddy Rocco Trio for the Dubonnet label, which was owned by the Dubonnet music publishing firm and used exclusively to plug their songs.[3]

In mid-1945, Eberle attempted to become partners in a band formed by sax player Dave Matthews. Matthews, unable to get quality booking under his own name, brought Eberle in on the deal. In May, however, Eberle received his draft notice, ending the venture.[4] Ironically, Eberle had just been rejected by his draft board earlier that year. In the army, Eberle served at Fort MacArthur in California.

Discharged from the service in mid-1946, Eberle formed his own orchestra that fall. Rosemary Calvin became female vocalist in fall 1947, with trumpet player Johnny Bond singing specialty numbers. Bond left the band in February 1948 to form his own orchestra, with Calvin joining him. Joan Marshall replaced Calvin in Eberle’s band. The orchestra recorded on the Signature label in 1948 but found little success, and Eberle disbanded in early 1949, after which he continued with his solo career.

In 1951, Eberle recorded with former Miller bandmate Tex Beneke’s orchestra and in 1970 joined them for a national tour. He often reunited with his former Miller bandmates for reunion shows. Eberle formed a new orchestra in the mid-1950s and continued working with bands on and off until his death from a heart attack in 1979 at age 60.

Notes

Bob changed the spelling of his last name to Eberly in 1939 due to an announcer who kept mispronouncing it. A third Eberle brother, Walter, briefly sang for Hal McIntyre in 1941. ↩︎

Eberle’s father had been a policeman in Mechanicville. ↩︎

No sources give dates on Eberle’s Dubonnet recordings, and extremely little information is available about the Dubonnet music publishing firm itself. They were active in the mid-1940s, and given Eberle’s timeline the recordings would have been made between November 1944, when the American Federation of Musicians’ recording ban ended, and the time he entered the service in May 1945. ↩︎

Despite the setback, Matthews continued with the band, which fell apart after only a few performances. ↩︎

Sources

- Simon, George T. The Big Bands. 4th ed. New York: Schirmer, 1981.

- Walker, Leo. The Wonderful Era of the Great Dance Bands. Garden City, New York: Doubleday, 1972.

- “Ray Eberle.” IMDb Accessed 28 May 2022.

- “Ray Eberle Is Married.” Down Beat 1 Aug. 1940: 11.

- “Campus Picks Top Chirps.” Billboard 2 May 1942: 19.

- “Ray Eberle Goes With Krupa.” Down Beat 15 Aug. 1942: 1.

- “Vaudeville Reviews: Orpheum, Los Angeles.” Billboard 16 Jan. 1943: 16.

- “Orchestra Notes.” Billboard 23 Jan. 1943: 23.

- “What Happened to Jan And Ray Shouldn't of.” Down Beat 1 Feb. 1943: 6.

- Chasins, Gladys. “Picture Tie-Ups for Music Machine Operators.” Billboard 13 Feb. 1943: 65.

- “Ray Eberle to Start Career In the Films.” Down Beat 15 Feb. 1943: 20.

- “Los Angeles Band Briefs.” Down Beat 15 Apr. 1943: 6.

- “Ray Eberle Singing with Herb Miller.” Billboard 24 Apr. 1943: 23.

- “Students Select Singers.” Billboard 5 Jun. 1943: 20.

- “Army Rejects Two Vocalists.” Down Beat 1 Mar. 1945: 6.

- “Ray Eberle Joins Dave Matthews in New Band Set-Up.” Billboard 28 Apr. 1945: 18.

- “Matthews Band Set With WMA Deal.” Down Beat 1 May 1945: 3.

- “Los Angeles Band Briefs.” Down Beat 15 Jun. 1945: 6.

- “Eberle At La Conga.” Down Beat 1 Jul. 1946: 1.

- “Strictly Ad Lib.” Down Beat 4 Nov. 1946: 5.

- “Music as Written.” Billboard 25 Jun. 1947: 30.

- “Calvin Joins Eberle.” Down Beat 17 Dec. 1947: 5.

- “Trade Tattle.” Down Beat 10 Mar. 1948: 22.

- “Eberle Disbands.” Down Beat 10 Mar. 1948: 22.

- “Ray Eberle Cuts With Tex Beneke.” Down Beat 10 Aug. 1951: 1.

- “Roseland Owner Sees A Boom.” Down Beat 18 Apr. 1957: 11.

- Downs, Bobbi. “Many to Attend Ray Eberle Show This Week-End.” The St. Petersburg Evening Independent [St. Petersburg, Florida] 21 Aug. 1958: 4B.

- “Miller Era Recalled by Eberle Repertoire.” The St. Petersburg Evening Independent [St. Petersburg, Florida] 7 Jul. 1960: 6C.

- “Funeral Services Today in Georgia for Ray Eberle.” The New London Day [New London, Connecticut] 28 Aug. 1979: 29.

- “United States Census, 1920,” FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:MVSQ-2BV : Sun Mar 10 21:30:47 UTC 2024), Entry for John A Eberle and Margaret L Eberle, 1920.

- “New York State Census, 1925,” FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:K9TP-FJT : Fri Mar 08 10:21:33 UTC 2024), Entry for Raymond Eberle, 1925.

- “United States Census, 1930,” FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:X4T8-SZV : Sat Mar 09 10:53:20 UTC 2024), Entry for John A Eberly and Margaret L Eberly, 1930.

- “Virginia, Marriage Certificates, 1936-1988,” FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:QK9F-Z8VZ : Mon Mar 11 01:32:31 UTC 2024), Entry for Raymond Richard Eberle and Jack Eberle, 02 May 1940.

- “United States Social Security Death Index,” database, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:JKD3-FPR : 7 January 2021), Raymond Eberle, Aug 1979; citing U.S. Social Security Administration, Death Master File, database (Alexandria, Virginia: National Technical Information Service, ongoing).